the one, the only, ARETHA FRANKLIN! this brought me to tears - so pure, so passionate, so powerful. a great way to say goodbye to 2015.

Thursday, December 31, 2015

Friday, December 25, 2015

special full moon on christmas day

today's full moon is the first on christmas day in 38 years. the year was 1977 - when Star Wars Episode IV was released!

without any spoilers - i really enjoyed the new star wars, the force awakens, released this holiday season. i enjoyed most of the new characters they introduced, including Rey, who is a major character. but how pathetic that she's not included by several retailers? DO BETTER HUMANS!

anyway, happy holidays, everyone!

|

| via NASA |

without any spoilers - i really enjoyed the new star wars, the force awakens, released this holiday season. i enjoyed most of the new characters they introduced, including Rey, who is a major character. but how pathetic that she's not included by several retailers? DO BETTER HUMANS!

|

| From Jamie Ford on twitter |

anyway, happy holidays, everyone!

Sunday, November 29, 2015

Cloudy with a chance of life: how to find alien life on distant exoplanets

This article was originally published in The Conversation on on 26th November 2015.

How do you go about hunting for life on another planet elsewhere in our galaxy? A useful starting point is to imagine looking from afar for signs of life on Earth. In a telescope like those we have on Earth, those aliens would likely just see the Earth and sun merged together into a single pale yellow dot.

If they were able to separate the Earth from the sun, they’d still only see a pale blue dot. There would be no way for them to image our planet’s surface and see life roving upon it.

However, those aliens could use spectroscopy, taking Earth’s light and breaking it into its component colours, to figure out what gases make up our atmosphere. Among these gases, they might hope to find a “biomarker”, something unusual and unexpected that could only be explained by the presence of life.

On Earth, the most obvious clue to the presence of life is the abundance of free oxygen in our atmosphere. Why oxygen? Because it is highly reactive and readily combines with other molecules on Earth’s surface and in our oceans. Without the constant resupply coming from life, the free oxygen in the atmosphere would largely disappear.

Biomarkers

But the story isn’t quite that simple. Life has existed on Earth for at least 3.5 billion years. For much of that time, however, oxygen levels were far lower than those seen today.

And oxygen alone is not enough to indicate life; there are many abiological processes that can contribute oxygen to a planet’s atmosphere.

For example, ultraviolet light could produce abundant oxygen in the atmosphere of a world covered with water, even if it was devoid of life.

The upshot of this is that a single gas does not a biomarker make. Instead, we must instead look for evidence of a chemical imbalance in a planet’s atmosphere, something that can not be explained by anything other than the presence of life.

Here on Earth, we have one: our atmosphere is not just rich in oxygen, but also contains significant traces of methane. While abundant oxygen or methane could easily be explained on a planet without life, we also know that methane and oxygen react with each other strongly and rapidly.

When you put them together, that reaction will cleanse the atmosphere of whichever is least common. So to maintain the amount of methane in our oxygen-rich atmosphere, you need a huge source of methane, replenishing it against oxygen’s depleting influence. The most likely explanation is life.

Observing exoplanetary atmospheres

If we find an exoplanet sufficiently similar to our own, there are several ways in which we could study its atmosphere to search for biomarkers.

When a planet passes directly between us and its host star, a small fraction of the star’s light will pass through the planet’s atmosphere on its way to Earth. If we could zoom in far enough, we would actually see the planet’s atmosphere as a translucent ring surrounding the dark spot that marks the body of the planet.

How much starlight passes through that ring gives us an indication of the atmosphere’s density and composition. What we get is a “transmission spectrum”, which is an absorption spectrum of the planetary atmosphere, illuminated by the background light of the star.

Our technology has only now become capable of collecting and analysing these spectra for the first time. As a result, our interpretation remains strongly limited by our telescopic capabilities and our burgeoning understanding of planetary atmospheres.

Despite the current challenges, the technique continues to develop with great success. In the past few years, astronomers have discovered a wide variety of different chemical species in the atmospheres of some of the biggest and baddest of the known transiting exoplanets.

Eclipses

Another approach involves observing a transiting planet and its star as they orbit one another. The goal here is to collect some observations when the planet is visible (but not in transit), and others when it is eclipsed by its star.

With some effort, astronomers can subtract one observation from the other, effectively cancelling the hugely dominant contribution of light from the star. Once that light is removed, what we have left is the day-side spectrum of the planet.

The future

Astronomers are constantly developing new techniques to glean information about exoplanetary atmospheres. One that shows particular potential, especially for the search for planets like our own, is the use of polarised light.

Most of the light we receive from planets is reflected, originating with the host star. The process of reflection brings with it a subtle benefit - the reflected light gains a degree of polarisation. Different surfaces yield different levels of polarisation, and that polarisation might just hold the key to finding the first oceans beyond the solar system.

These methods are still severely constrained by two factors: the relative faintness of the exoplanets, and their proximity to their host star. The ongoing story of exoplanetary science is therefore heavily focused on overcoming these observational challenges.

Further down the line, advances in technology and the next generation of telescopes may allow the light from an Earth-like planet to be seen directly. At that point, the task becomes (slightly) easier, in part because the planet can be observed for far longer, rather than just relying on eclipse/transit observations.

But even then, spectroscopy will be the way to go; the planets will still be just pale blue dots.

What we have seen so far

The exoplanets we have discovered to date are highly inhospitable to life as we know it. None of the planets studied so far would even be habitable to the most extreme of extremophiles.

The planets whose atmospheres we have studied are primarily “hot Jupiters”, giant planets orbiting perilously close to their host stars. As they skim their host’s surface, they whizz around with periods of just a few days, yielding transits and eclipses with every orbit.

Because of the vast amounts of energy they receive from their hosts, many of these “hot Jupiters” are enormous, inflated far beyond the scale of our solar system’s largest planet. That size, that heat and their speed, make them the easiest targets for our observations.

But as our technology has improved, it has also become possible to observe, through painstaking effort, some smaller planets, known as “super-Earths”.

Atmospheres of distant planets…

The hot Jupiter HD189733 has one of the best understood planetary atmospheres beyond the solar system.

Observations by the Hubble Space Telescope, in 2013, suggest a deep-blue world, with a thick atmosphere of silicate vapour. Other studies have shown its atmosphere to contain significant amounts of water vapour, and carbon dioxide.

Overall, however, it appears to be a hydrogen-rich gas giant like Jupiter, albeit super-heated, with cloud tops exceeding 1,000 degrees. Beneath the cloud turps lies a widespread dust layer, featuring silicate and metallic salt compounds.

The young giant planets in the HR8799 system appear to have hydrogen-rich but complex atmospheres, with compounds such as methane, carbon monoxide and water. They are likely larger, younger, and hotter versions of our own giant planets - with their own unique subtleties.

For the super-Earth GJ1214b the lesson is to be careful about making conclusions. Early suggestions that this might be a “water world” or have a cloudless hydrogen atmosphere have since been superseded by models featuring a haze of hydrocarbon compounds (like on Titan), or grains of potassium salt or zinc sulphide.

While the search for Earth-like planets continues using ground- and space-based telescopes, exoplanetary scientists are eagerly awaiting the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope JWST.

That immense telescope, scheduled for launch in around October 2018, could mark the true beginning of the exciting search for distant atmospheric biomarkers and exoplanetary life.

Cloudy with a chance of life:

by Brad Carter, Amanda Bauer, & Jonti Horner

How do you go about hunting for life on another planet elsewhere in our galaxy? A useful starting point is to imagine looking from afar for signs of life on Earth. In a telescope like those we have on Earth, those aliens would likely just see the Earth and sun merged together into a single pale yellow dot.

If they were able to separate the Earth from the sun, they’d still only see a pale blue dot. There would be no way for them to image our planet’s surface and see life roving upon it.

However, those aliens could use spectroscopy, taking Earth’s light and breaking it into its component colours, to figure out what gases make up our atmosphere. Among these gases, they might hope to find a “biomarker”, something unusual and unexpected that could only be explained by the presence of life.

On Earth, the most obvious clue to the presence of life is the abundance of free oxygen in our atmosphere. Why oxygen? Because it is highly reactive and readily combines with other molecules on Earth’s surface and in our oceans. Without the constant resupply coming from life, the free oxygen in the atmosphere would largely disappear.

Biomarkers

But the story isn’t quite that simple. Life has existed on Earth for at least 3.5 billion years. For much of that time, however, oxygen levels were far lower than those seen today.

And oxygen alone is not enough to indicate life; there are many abiological processes that can contribute oxygen to a planet’s atmosphere.

|

| The concentration of oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere over the last billion years. As a reference, the dashed red line shows the present concentration of 21%. Wikimedia |

For example, ultraviolet light could produce abundant oxygen in the atmosphere of a world covered with water, even if it was devoid of life.

The upshot of this is that a single gas does not a biomarker make. Instead, we must instead look for evidence of a chemical imbalance in a planet’s atmosphere, something that can not be explained by anything other than the presence of life.

Here on Earth, we have one: our atmosphere is not just rich in oxygen, but also contains significant traces of methane. While abundant oxygen or methane could easily be explained on a planet without life, we also know that methane and oxygen react with each other strongly and rapidly.

When you put them together, that reaction will cleanse the atmosphere of whichever is least common. So to maintain the amount of methane in our oxygen-rich atmosphere, you need a huge source of methane, replenishing it against oxygen’s depleting influence. The most likely explanation is life.

Observing exoplanetary atmospheres

If we find an exoplanet sufficiently similar to our own, there are several ways in which we could study its atmosphere to search for biomarkers.

When a planet passes directly between us and its host star, a small fraction of the star’s light will pass through the planet’s atmosphere on its way to Earth. If we could zoom in far enough, we would actually see the planet’s atmosphere as a translucent ring surrounding the dark spot that marks the body of the planet.

How much starlight passes through that ring gives us an indication of the atmosphere’s density and composition. What we get is a “transmission spectrum”, which is an absorption spectrum of the planetary atmosphere, illuminated by the background light of the star.

Our technology has only now become capable of collecting and analysing these spectra for the first time. As a result, our interpretation remains strongly limited by our telescopic capabilities and our burgeoning understanding of planetary atmospheres.

Despite the current challenges, the technique continues to develop with great success. In the past few years, astronomers have discovered a wide variety of different chemical species in the atmospheres of some of the biggest and baddest of the known transiting exoplanets.

|

| Many exoplanets may have no atmosphere at all. NASA/JPL-Caltech |

Eclipses

Another approach involves observing a transiting planet and its star as they orbit one another. The goal here is to collect some observations when the planet is visible (but not in transit), and others when it is eclipsed by its star.

With some effort, astronomers can subtract one observation from the other, effectively cancelling the hugely dominant contribution of light from the star. Once that light is removed, what we have left is the day-side spectrum of the planet.

|

| [Star + Planet] - [Star] = [Planet] NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (SSC/Caltech) |

The future

Astronomers are constantly developing new techniques to glean information about exoplanetary atmospheres. One that shows particular potential, especially for the search for planets like our own, is the use of polarised light.

Most of the light we receive from planets is reflected, originating with the host star. The process of reflection brings with it a subtle benefit - the reflected light gains a degree of polarisation. Different surfaces yield different levels of polarisation, and that polarisation might just hold the key to finding the first oceans beyond the solar system.

|

| By rotating a polarising filter, we can block light of certain polarisation. This is how polarised sunglasses cut the glare from puddles and the ocean on a sunny day. Wikimedia, CC BY-SA |

These methods are still severely constrained by two factors: the relative faintness of the exoplanets, and their proximity to their host star. The ongoing story of exoplanetary science is therefore heavily focused on overcoming these observational challenges.

Further down the line, advances in technology and the next generation of telescopes may allow the light from an Earth-like planet to be seen directly. At that point, the task becomes (slightly) easier, in part because the planet can be observed for far longer, rather than just relying on eclipse/transit observations.

But even then, spectroscopy will be the way to go; the planets will still be just pale blue dots.

What we have seen so far

The exoplanets we have discovered to date are highly inhospitable to life as we know it. None of the planets studied so far would even be habitable to the most extreme of extremophiles.

The planets whose atmospheres we have studied are primarily “hot Jupiters”, giant planets orbiting perilously close to their host stars. As they skim their host’s surface, they whizz around with periods of just a few days, yielding transits and eclipses with every orbit.

Because of the vast amounts of energy they receive from their hosts, many of these “hot Jupiters” are enormous, inflated far beyond the scale of our solar system’s largest planet. That size, that heat and their speed, make them the easiest targets for our observations.

But as our technology has improved, it has also become possible to observe, through painstaking effort, some smaller planets, known as “super-Earths”.

Atmospheres of distant planets…

The hot Jupiter HD189733 has one of the best understood planetary atmospheres beyond the solar system.

|

| Artists impression of the broiling blue marble, HD 189733 b. NASA, ESA, M. Kornmesser |

Observations by the Hubble Space Telescope, in 2013, suggest a deep-blue world, with a thick atmosphere of silicate vapour. Other studies have shown its atmosphere to contain significant amounts of water vapour, and carbon dioxide.

Overall, however, it appears to be a hydrogen-rich gas giant like Jupiter, albeit super-heated, with cloud tops exceeding 1,000 degrees. Beneath the cloud turps lies a widespread dust layer, featuring silicate and metallic salt compounds.

The young giant planets in the HR8799 system appear to have hydrogen-rich but complex atmospheres, with compounds such as methane, carbon monoxide and water. They are likely larger, younger, and hotter versions of our own giant planets - with their own unique subtleties.

|

| A direct image of the four planets known to orbit the star HR 8799. Ben Zuckerman |

For the super-Earth GJ1214b the lesson is to be careful about making conclusions. Early suggestions that this might be a “water world” or have a cloudless hydrogen atmosphere have since been superseded by models featuring a haze of hydrocarbon compounds (like on Titan), or grains of potassium salt or zinc sulphide.

While the search for Earth-like planets continues using ground- and space-based telescopes, exoplanetary scientists are eagerly awaiting the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope JWST.

That immense telescope, scheduled for launch in around October 2018, could mark the true beginning of the exciting search for distant atmospheric biomarkers and exoplanetary life.

Thursday, November 26, 2015

100 years of general relativity

a nice animated video to explain einstein's general relativity in 3 short minutes!

you might also be interested in a recent conversation article by michael brown on "why einstein's general relativity is such a popular target for cranks".

i get A LOT of emails from random people claiming they have proven einstein wrong, and this offers some insight as to why that might be.

you might also be interested in a recent conversation article by michael brown on "why einstein's general relativity is such a popular target for cranks".

i get A LOT of emails from random people claiming they have proven einstein wrong, and this offers some insight as to why that might be.

Tuesday, November 10, 2015

sky schemes: a song

My unofficial hack at last week's .Astronomy 7 conference in sydney was to perform a song i wrote recently called Sky Schemes. Luckily, Becky recorded it for all to hear!

Sky Schemes

By Amanda Bauer (2015)

On winter nights when I was a girl

I’d go to her house after school

We’d play game, make things, discover our dreams

I’d walk home through the dark remembering our schemes

I’d look up at the stars, shining overhead

Make constellations that I saw instead

Of those Greek ones, Islamic ones, they are so old

There are native ones, Indigenous ones, but we’re seldom told

I made one up. It was a bird, wings spread wide

I’d look for it, find it, feel so much pride

So look up at the stars, shining overhead

Make constellations that you see instead

There are new ones, trues ones, you will see first

Share them with us, through us, satisfy your thirst

To know things, understand, how we are here

No true answer you’ll find, but it will become clear

The questions that matter are changing all the time

Rely on your instincts, empower your mind

And then look up at the stars, shining overhead

Make constellations that you see instead

also, another quick announcement that you might suspect from the photo below... go to THIS LINK and keep exploring until you uncover the surprise :) this reveal was also made as a result of .Astronomy hack day.

Sky Schemes

By Amanda Bauer (2015)

On winter nights when I was a girl

I’d go to her house after school

We’d play game, make things, discover our dreams

I’d walk home through the dark remembering our schemes

I’d look up at the stars, shining overhead

Make constellations that I saw instead

Of those Greek ones, Islamic ones, they are so old

There are native ones, Indigenous ones, but we’re seldom told

I made one up. It was a bird, wings spread wide

I’d look for it, find it, feel so much pride

So look up at the stars, shining overhead

Make constellations that you see instead

There are new ones, trues ones, you will see first

Share them with us, through us, satisfy your thirst

To know things, understand, how we are here

No true answer you’ll find, but it will become clear

The questions that matter are changing all the time

Rely on your instincts, empower your mind

And then look up at the stars, shining overhead

Make constellations that you see instead

|

| Photo by Andy Green |

|

| Photo by Andy Green |

also, another quick announcement that you might suspect from the photo below... go to THIS LINK and keep exploring until you uncover the surprise :) this reveal was also made as a result of .Astronomy hack day.

|

| Photo by Andy Green |

.

Tuesday, October 13, 2015

Sunday, October 11, 2015

berkeley astronomer guilty of sexual harassment

the best thing i can say is that sexual harassment in academia is being discussed in the media and it's finally out in the open that berkeley's well known exopolanet astronomer, geoff marcy, is a serial sexual harasser.

you see, for YEARS (since 2001) reports of his inappropriate actions have been known to his undergraduate and graduate students and postdocs, and formal complaints were brought to him in 2004. he was told that his massages and touches and attempted kisses and GROPES were unwanted and inappropriate. he knew this, even though in his recent semi-apology he tries to express "how painful it is for me to realize that I was a source of distress for any of my women colleagues, however unintentional." i'm calling bullshit.

surely his senior colleagues knew these formal complaints had been filed as his reputation raged among the international astronomers who worked on his teams. but did any of his colleagues step up and say to him "Dude, this is not cool. STOP IT!" nothing of the sort is on record, although i'd love to be corrected on this.

so marcy persisted.

and what happened during the last 15 years? an informal network of women trying to protect each other from his behaviour naturally formed, warning younger colleagues to "watch out" for him at major conferences.

as the altlantic describes,

the sad reality is that berkeley is moving forward with NO disciplinary action AT ALL! this i do not understand. YET AGAIN the burden to "deal" with the repercussions of this horrific behaviour is placed on the victims. <::sarcastic truthiness::=""> poor mr famous scientist, please act within the rules already in place for all scientists in this university or else we may just have to be courageous enough to discipline you. </>

i can guarantee that marcy is not the only sexual predator whose actions have been protected by cowardly colleagues and universities. two years ago i wrote about my personal experience as a victim of sexual harassment as a PhD student at the university of texas at austin (UT). i took steps to lodge a formal complaint, but was thwarted by senior faculty. i chose to just "deal" with it and get on with my studies, knowing that there had been others and would be more victims of this man's pathetic advances.

i became part of the internal network of women warning other women to avoid him, while male students sat by saying things like "that sucks" and senior staff went on protecting him - for DECADES.

YES IT DOES SUCK. and it's not fair. this man continued to work and teach at UT and FINALLY was lightly forced into early retirement so the department could once and for all stop figuring out how to suppress the complaints of his victims and his continuing bad behaviours. this professor was not famous in his field. he was not bringing in large grants. his research was nothing of note. but he was surrounded by a "good old boys" network that protected him just the same.

the only action of consequence against marcy so far is that he has been asked to skip one of the biggest professional astronomy meetings in the world this january. imagine this - instead of telling women to be cautious around known sexual harassers - TELL THE HARASSERS TO STOP FUCKING HARASSING PEOPLE and/or STAY AWAY!

so thank you to yale astronomer and American Astronomical Society (AAS) President Meg Urry who says this about her intolerance for harassment at the conference:

Come on astronomers, let's expect MORE from our senior colleagues and tell them so. it's worth it to hold them to humane behaviour standards, regardless of their scientific achievements or potential.

you see, for YEARS (since 2001) reports of his inappropriate actions have been known to his undergraduate and graduate students and postdocs, and formal complaints were brought to him in 2004. he was told that his massages and touches and attempted kisses and GROPES were unwanted and inappropriate. he knew this, even though in his recent semi-apology he tries to express "how painful it is for me to realize that I was a source of distress for any of my women colleagues, however unintentional." i'm calling bullshit.

surely his senior colleagues knew these formal complaints had been filed as his reputation raged among the international astronomers who worked on his teams. but did any of his colleagues step up and say to him "Dude, this is not cool. STOP IT!" nothing of the sort is on record, although i'd love to be corrected on this.

so marcy persisted.

and what happened during the last 15 years? an informal network of women trying to protect each other from his behaviour naturally formed, warning younger colleagues to "watch out" for him at major conferences.

as the altlantic describes,

Marcy leveraged his considerable fame and power in the world of astronomy to build a nearly consequence-free bubble around himself.

the sad reality is that berkeley is moving forward with NO disciplinary action AT ALL! this i do not understand. YET AGAIN the burden to "deal" with the repercussions of this horrific behaviour is placed on the victims. <::sarcastic truthiness::=""> poor mr famous scientist, please act within the rules already in place for all scientists in this university or else we may just have to be courageous enough to discipline you. </>

i can guarantee that marcy is not the only sexual predator whose actions have been protected by cowardly colleagues and universities. two years ago i wrote about my personal experience as a victim of sexual harassment as a PhD student at the university of texas at austin (UT). i took steps to lodge a formal complaint, but was thwarted by senior faculty. i chose to just "deal" with it and get on with my studies, knowing that there had been others and would be more victims of this man's pathetic advances.

i became part of the internal network of women warning other women to avoid him, while male students sat by saying things like "that sucks" and senior staff went on protecting him - for DECADES.

YES IT DOES SUCK. and it's not fair. this man continued to work and teach at UT and FINALLY was lightly forced into early retirement so the department could once and for all stop figuring out how to suppress the complaints of his victims and his continuing bad behaviours. this professor was not famous in his field. he was not bringing in large grants. his research was nothing of note. but he was surrounded by a "good old boys" network that protected him just the same.

the only action of consequence against marcy so far is that he has been asked to skip one of the biggest professional astronomy meetings in the world this january. imagine this - instead of telling women to be cautious around known sexual harassers - TELL THE HARASSERS TO STOP FUCKING HARASSING PEOPLE and/or STAY AWAY!

so thank you to yale astronomer and American Astronomical Society (AAS) President Meg Urry who says this about her intolerance for harassment at the conference:

Sexual harassment usually involves a question of a power imbalance. [...] And one of the saddest things I’ve ever seen is when a young woman realizes that the extra attention she is receiving from an older, male astronomer is not related to her science.

Come on astronomers, let's expect MORE from our senior colleagues and tell them so. it's worth it to hold them to humane behaviour standards, regardless of their scientific achievements or potential.

Sunday, September 13, 2015

collecting SAMI galaxies

I've been up at Siding Spring Observatory visiting this beauty this week.

I enjoy walking around the dome's catwalk to see the views in all directions.

The first night provided a lovely (cloudy) sunset.

But then the skies cleared BEAUTIFULLY for most of the observing run and the Milky Way glowed brilliantly across the early evening sky.

We have been using the SAMI instrument during this run to observe over 100 galaxies so far!

Kristin was the telescope operator for the beginning of the run. Here she is with the original control panel that was installed 40 years ago! while it still looks roughly the same - systems and displays have been upgraded over the years :)

we had some time for enjoying the clear night skies while exposing with the big telescope

And we may have started to write a few songs for "SAMI - then Musical" ;)

|

| The dome of the 4-metre Anglo-Australian Telescope |

|

| Hello from the catwalk! |

But then the skies cleared BEAUTIFULLY for most of the observing run and the Milky Way glowed brilliantly across the early evening sky.

We have been using the SAMI instrument during this run to observe over 100 galaxies so far!

|

| Perched at Prime Focus with SAMI |

we had some time for enjoying the clear night skies while exposing with the big telescope

|

| The Magellanic Clouds and the AAT dome. (Credit: Jesse van de Sande) |

|

| Milky Way (Credit: Angel Lopez-Sanchez) |

Monday, August 10, 2015

A 2dF night at the Anglo-Australian Telescope

A new video from AAO!

"A 2dF night at the AAT" assembles 14 time-lapse sequences taken at the 4-metre Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) located at Siding Spring Observatory NSW, Australia. This time-lapse video shows not only how the Two Degree Field (2dF) instrument works but also how the AAT and the telescope dome move in tandem, and the beauty of the Southern Sky in spring and summer.

The video is 2min 50sec long and combines more than 4000 frames obtained using a CANON EOS 600D with a 10-20mm wide-angle lens. All sequences were taken during September and November 2011 by astronomer Dr Ángel R. López-Sánchez while he was working as the 2dF support astronomer for the AAT. The music is the song “Blue Raider” from Composer Cesc Villà's album “Epic Soul Factory”

Saturday, August 8, 2015

the star talker - neil degrasse tyson

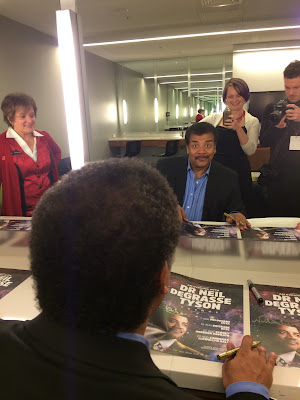

what a fun, almost surreal evening talking with Neil DeGrasse Tyson.

He reminded us to "look the hell up every once in a while" and not to take evidence of science and technology in our everyday lives (phones!) for granted.

I didn't realize for the first few minutes that we were on the HUGE screen behind us on stage!

one of the best parts about spending time with neil is realising that he is constantly observing the world around him and thinking about it, questioning it, interpreting it - not taking it at face value. it's something we should all do more, as it keeps us present in the moment and prevents us from not appreciating all the amazing things around us.

I'll host his next show in brisbane next weekend, so there's still time to let me know what questions you would ask him if you had the chance!

also, should i wear the boots again, or change it up? serious questions of the universe....

|

| pre-show with Neil deGrasse Tyson |

I didn't realize for the first few minutes that we were on the HUGE screen behind us on stage!

one of the best parts about spending time with neil is realising that he is constantly observing the world around him and thinking about it, questioning it, interpreting it - not taking it at face value. it's something we should all do more, as it keeps us present in the moment and prevents us from not appreciating all the amazing things around us.

|

| With Neil DeGrasse Tyson after our conversation in Melbourne, thanks to Think Inc |

also, should i wear the boots again, or change it up? serious questions of the universe....

Wednesday, August 5, 2015

Hosting Neil DeGrasse Tyson

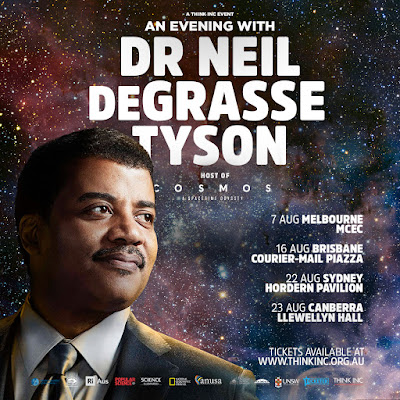

dr neil degrasse tyson is one of the most recognised scientists in the world right now and he has recently embarked on an australian tour!

i'm thrilled to report that i will be hosting two of his shows: August 7th in Melbourne and August 16th in Brisbane!

there are still tickets available for each show, so if you're around, please join us!

what does hosting mean? i will pop up on stage first and welcome everyone to the event then introduce neil and invite him to the stage. he and i will then sit in a couple comfy chairs and have an hour long conversation on topics ranging from pluto to science education to alien life to the (lack of) edge of the universe!

then a few audience members will have a chance to ask him questions as well.

i'm thrilled for this opportunity and will hopefully have a full report after the events are finished. here we go...!

i'm thrilled to report that i will be hosting two of his shows: August 7th in Melbourne and August 16th in Brisbane!

there are still tickets available for each show, so if you're around, please join us!

what does hosting mean? i will pop up on stage first and welcome everyone to the event then introduce neil and invite him to the stage. he and i will then sit in a couple comfy chairs and have an hour long conversation on topics ranging from pluto to science education to alien life to the (lack of) edge of the universe!

then a few audience members will have a chance to ask him questions as well.

i'm thrilled for this opportunity and will hopefully have a full report after the events are finished. here we go...!

Sunday, July 26, 2015

Journey to the edge of a forming galaxy

in early july i spent two weeks as "scientist in residence" at the ABC as a result of the Top 5 Under 40 award. the main project i worked on was producing a science ninja adventure story that went live on the science show on radio national yesterday afternoon!

LISTEN HERE:

journey to the edge of a forming galaxy (website)

journey to the edge of a forming galaxy (mp3)

long time readers may remember the seeds of this story from a blog post in 2010. you never know what direction random inspiration will go!

transforming the written story into something radio-ready was an interesting challenge. phrases that look lovely on the page do not sound smooth or conversational when spoken out loud. i wrote many versions of the story (in less than 2 days) before settling into one that i could read out loud comfortably.

once the story was ready, i had the amazing luck of booking an entire afternoon in the studio with award-winning sound engineer Russell Stapleton. i had shared an early draft of the story with him and he came prepared with directories of "space and ninja" sounds that he had been working with for the last 20 years! he really made the story come alive and it was fascinating to watch him work. such a unique experience to work with him to create the depth of sound you hear throughout the story.

the science show producer asked me for some unique artwork to display with the story on the webpage, since a regular galaxy image would be a bit boring. i was busy at a workshop during the couple days i had to produce the image, so i asked twitter for volunteers to help. they certainly came through - the images are displayed through this post. thanks so much to Mischa Andrews and Glen Nagle!

Hope you enjoy the adventure!

LISTEN HERE:

journey to the edge of a forming galaxy (website)

journey to the edge of a forming galaxy (mp3)

|

| Artwork by Mischa Andrews from photo by Jenny Gabache and galaxy image by David Malin |

long time readers may remember the seeds of this story from a blog post in 2010. you never know what direction random inspiration will go!

transforming the written story into something radio-ready was an interesting challenge. phrases that look lovely on the page do not sound smooth or conversational when spoken out loud. i wrote many versions of the story (in less than 2 days) before settling into one that i could read out loud comfortably.

|

| Artwork by Glen Nagle |

once the story was ready, i had the amazing luck of booking an entire afternoon in the studio with award-winning sound engineer Russell Stapleton. i had shared an early draft of the story with him and he came prepared with directories of "space and ninja" sounds that he had been working with for the last 20 years! he really made the story come alive and it was fascinating to watch him work. such a unique experience to work with him to create the depth of sound you hear throughout the story.

the science show producer asked me for some unique artwork to display with the story on the webpage, since a regular galaxy image would be a bit boring. i was busy at a workshop during the couple days i had to produce the image, so i asked twitter for volunteers to help. they certainly came through - the images are displayed through this post. thanks so much to Mischa Andrews and Glen Nagle!

|

| Put together by Glen Nagle from photo by Jenny Gabache and galaxy image by David Malin |

Hope you enjoy the adventure!

Sunday, July 19, 2015

2015 David Malin Award Winners

Here is the first batch of winning astrophotos from the annual David Malin Awards contest. These are absolutely stunning captures from non-professional astronomers around australia!

|

| Overall Winner: "Stellar Riches" by Troy Casswell |

|

| Deep sky winner: "The Fighting Dragons of Ara" by Andrew Campbell |

|

| Nightscape winner: "Aurora Treescape" by James Garlick |

|

| Solar system winner: "Solar Crown" by Peter Ward |

Saturday, July 18, 2015

seeing the universe through spectroscopic eyes

I published this article at The Conversation last week, reproduced here for your enjoyment :) Original article link.

Seeing the Universe Through Spectroscopic Eyes

When you look up on a clear night and see stars, what are you really looking at? A twinkling pinprick of light with a hint of colour?

Imagine looking at a starry sky with eyes like prisms that separate the light from each star into its full rainbow of colour. Astronomers have built instruments to do just that, and spectroscopy is one of the most powerful tools in the astronomer’s box.

The technique might not produce the well-known pretty pictures sent down by the Hubble Space Telescope, but for astronomers, a spectrum is worth a thousand pictures.

Visible spectra reveal huge amounts of information about objects in the distant cosmos that we can’t learn any other way.

So what is spectroscopy?

Spectroscopy is the process of separating starlight into its constituent wavelengths, like a prism turning sunlight into a rainbow. The familiar colours of the rainbow correspond to different wavelengths of visible light.

The human eye is sensitive to the visible spectrum – a narrow range of frequencies among the entire electromagnetic spectrum. The visible spectrum covers wavelengths of roughly 390 nanometers to 780 nanometers (astronomers often use units of Angstroms (10-10), so visible light spans 3,900 to 7,800 Angstroms).

Once visible starlight reaches the curved primary mirror of a telescope, it is reflected toward the focal point and can then be directed anywhere. If the light is sent directly to a camera, an image of the night sky is seen on a computer screen as a result.

If the light is instead sent through a spectrograph before it hits the camera, then the light from the astronomical object gets separated into its basic parts.

A very simple spectrograph was used by Issac Newton in the 1660s when he dispersed light with a glass prism. Modern spectrographs consist of a series of optics, a dispersing element and a camera at the end. The light is digitised and sent to a computer, which astronomers use to inspect and analyse the resulting spectra.

The video (above) shows the path of distant starlight through the 4-metre Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) and a typical spectrograph, revealing real data at the end.

What do spectra teach us?

A spectrum allows astronomers to determine many things about the object being viewed, such as how far away it is, its chemical makeup, age, formation history, temperature and more. While every astronomical object has a unique rainbow fingerprint, some general properties are universal.

Here we examine the galaxy spectra shown in the video. The spectrum of a galaxy is the combined light from its billions of stars and all other radiating matter in the galaxy, such as gas and dust.

In the top spectrum you can see a few strong spikes. These are called “emission lines” and occur at discrete wavelengths due to the atomic structure of atoms as electrons jump between energy levels.

The hydrogen spectrum is particularly important because 90% of the normal matter in the universe is hydrogen. Because of the details of hydrogen’s atomic structure, we recognise the strong hydrogen-alpha emission line at roughly 7,500 Angstroms in the top spectrum image.

In a galaxy, only the youngest, biggest stars are hot enough to excite surrounding hydrogen gas enough that the electrons populate the third energy level, before falling to the second lowest, thus emitting a hydrogen-alpha photon.

Because of this, we know the strength of the hydrogen-alpha line in a galaxy’s spectrum indicates how many very young stars there are in the galaxy. Since the bottom spectrum shows no hydrogen-alpha emission, we can conclude that the bottom galaxy is not sparking new life in the form of shining stars, while the top galaxy harbours several hard working stellar nurseries.

In the bottom spectrum you can see a number dips. These are called “absorption lines” because they appear in the spectrum if there is anything between the light’s source and the observer on Earth absorbing the light. Absorbing material could be the extended layers of a star or interstellar clouds of gas or dust.

The absorption lines close to each other below 5,000 Angstroms in the bottom spectrum are the calcium H and K lines and can be used to determine how quickly stars are zooming around the galaxy.

In a galaxy how far away?

A basic piece of information derived from a spectrum is the distance to the galaxy, or specifically, how much the light has stretched during its journey to Earth. Because the universe is expanding, the light emitted by the galaxy is stretched toward redder wavelengths as it innocently moves across space. We measure this as redshift.

To determine the exact distance of a galaxy, astronomers measure the well-studied pattern of absorption and emission lines in the observed spectrum and compare it to the laboratory wavelengths of these features on Earth. The difference tells how much the light was stretched, and therefore how long the light was travelling through space, and consequently how far away the galaxy is.

In the top galaxy spectrum mentioned earlier, we measure the strong red emission line of hydrogen-alpha to be at a wavelength of roughly 7,450 Angstroms. Since we know that line has a rest wavelength of 6,563 Angstroms, we calculate a redshift of 0.13, which means the light was travelling for 1.7 billion years before it reached our lucky telescope. The galaxy emitted that light when the universe was roughly 11.8 billion years old.

Australia’s strength in spectroscopy

Australia has led the way internationally for spectroscopic technology development for the last 20 years, largely due to the use of fibre optics to direct galaxy light from the telescope structure to the spectrograph.

A huge advantage of using optical fibres is that more than one spectrum can be obtained simultaneously, drastically improving the efficiency of the telescope observing time.

Australian astronomers have also led the world in building robotic technologies to position the individual optical fibres. With these, the AAT and the UK Schmidt Telescopes (both located at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales) have collected spectra for a third of all the 2.5 million galaxy spectra that humans have ever observed.

While my own research uses hundreds of thousands of galaxy spectra for individual projects, it still amazes me think that each one of these spectra are composite collections of light created by hundreds of billions of stars gravitationally bound together in a single swirling galaxy, many similar to our own Milky Way home.

Seeing the Universe Through Spectroscopic Eyes

When you look up on a clear night and see stars, what are you really looking at? A twinkling pinprick of light with a hint of colour?

Imagine looking at a starry sky with eyes like prisms that separate the light from each star into its full rainbow of colour. Astronomers have built instruments to do just that, and spectroscopy is one of the most powerful tools in the astronomer’s box.

The technique might not produce the well-known pretty pictures sent down by the Hubble Space Telescope, but for astronomers, a spectrum is worth a thousand pictures.

Visible spectra reveal huge amounts of information about objects in the distant cosmos that we can’t learn any other way.

So what is spectroscopy?

Spectroscopy is the process of separating starlight into its constituent wavelengths, like a prism turning sunlight into a rainbow. The familiar colours of the rainbow correspond to different wavelengths of visible light.

The human eye is sensitive to the visible spectrum – a narrow range of frequencies among the entire electromagnetic spectrum. The visible spectrum covers wavelengths of roughly 390 nanometers to 780 nanometers (astronomers often use units of Angstroms (10-10), so visible light spans 3,900 to 7,800 Angstroms).

Once visible starlight reaches the curved primary mirror of a telescope, it is reflected toward the focal point and can then be directed anywhere. If the light is sent directly to a camera, an image of the night sky is seen on a computer screen as a result.

If the light is instead sent through a spectrograph before it hits the camera, then the light from the astronomical object gets separated into its basic parts.

A very simple spectrograph was used by Issac Newton in the 1660s when he dispersed light with a glass prism. Modern spectrographs consist of a series of optics, a dispersing element and a camera at the end. The light is digitised and sent to a computer, which astronomers use to inspect and analyse the resulting spectra.

The video (above) shows the path of distant starlight through the 4-metre Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) and a typical spectrograph, revealing real data at the end.

What do spectra teach us?

A spectrum allows astronomers to determine many things about the object being viewed, such as how far away it is, its chemical makeup, age, formation history, temperature and more. While every astronomical object has a unique rainbow fingerprint, some general properties are universal.

|

| Top shows a spiral galaxy spectrum. Bottom shows non-star-forming galaxy spectrum. Screenshot from Australian Astronomical Observatory video above |

Here we examine the galaxy spectra shown in the video. The spectrum of a galaxy is the combined light from its billions of stars and all other radiating matter in the galaxy, such as gas and dust.

In the top spectrum you can see a few strong spikes. These are called “emission lines” and occur at discrete wavelengths due to the atomic structure of atoms as electrons jump between energy levels.

The hydrogen spectrum is particularly important because 90% of the normal matter in the universe is hydrogen. Because of the details of hydrogen’s atomic structure, we recognise the strong hydrogen-alpha emission line at roughly 7,500 Angstroms in the top spectrum image.

In a galaxy, only the youngest, biggest stars are hot enough to excite surrounding hydrogen gas enough that the electrons populate the third energy level, before falling to the second lowest, thus emitting a hydrogen-alpha photon.

Because of this, we know the strength of the hydrogen-alpha line in a galaxy’s spectrum indicates how many very young stars there are in the galaxy. Since the bottom spectrum shows no hydrogen-alpha emission, we can conclude that the bottom galaxy is not sparking new life in the form of shining stars, while the top galaxy harbours several hard working stellar nurseries.

In the bottom spectrum you can see a number dips. These are called “absorption lines” because they appear in the spectrum if there is anything between the light’s source and the observer on Earth absorbing the light. Absorbing material could be the extended layers of a star or interstellar clouds of gas or dust.

The absorption lines close to each other below 5,000 Angstroms in the bottom spectrum are the calcium H and K lines and can be used to determine how quickly stars are zooming around the galaxy.

In a galaxy how far away?

A basic piece of information derived from a spectrum is the distance to the galaxy, or specifically, how much the light has stretched during its journey to Earth. Because the universe is expanding, the light emitted by the galaxy is stretched toward redder wavelengths as it innocently moves across space. We measure this as redshift.

To determine the exact distance of a galaxy, astronomers measure the well-studied pattern of absorption and emission lines in the observed spectrum and compare it to the laboratory wavelengths of these features on Earth. The difference tells how much the light was stretched, and therefore how long the light was travelling through space, and consequently how far away the galaxy is.

|

| The absorption lines ‘shift’ the farther away an object is, giving us an indication of its distance from us. Georg Wiora (Dr. Schorsch) |

In the top galaxy spectrum mentioned earlier, we measure the strong red emission line of hydrogen-alpha to be at a wavelength of roughly 7,450 Angstroms. Since we know that line has a rest wavelength of 6,563 Angstroms, we calculate a redshift of 0.13, which means the light was travelling for 1.7 billion years before it reached our lucky telescope. The galaxy emitted that light when the universe was roughly 11.8 billion years old.

Australia’s strength in spectroscopy

Australia has led the way internationally for spectroscopic technology development for the last 20 years, largely due to the use of fibre optics to direct galaxy light from the telescope structure to the spectrograph.

A huge advantage of using optical fibres is that more than one spectrum can be obtained simultaneously, drastically improving the efficiency of the telescope observing time.

Australian astronomers have also led the world in building robotic technologies to position the individual optical fibres. With these, the AAT and the UK Schmidt Telescopes (both located at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales) have collected spectra for a third of all the 2.5 million galaxy spectra that humans have ever observed.

While my own research uses hundreds of thousands of galaxy spectra for individual projects, it still amazes me think that each one of these spectra are composite collections of light created by hundreds of billions of stars gravitationally bound together in a single swirling galaxy, many similar to our own Milky Way home.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)